On the 21st October 1916 Count Karl von Stürgkh was murdered by Friedrich Wolfgang Adler.

Stürgkh, whose family originated from the Upper Palatinate, had been born on 30th October 1859. The family owned vast estates in the Halbenrain region of Südoststeiermark in the Austrian state of Styria. The family had longed served the Habsburgs and Stürgkh was elected a member of the Austrian Imperial Council in 1891.

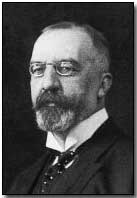

Count Karl von Stürgkh

A well respected politician in Imperial circles, Stürgkh served as minister for education in the cabinets of Count Richard von Bienerth-Schmerling and Paul Gautsch von Frankenthurn between 1909 and 1911. Internal problems in the Dual Monarchy caused increasing unrest and by 1911 rising food prices had resulted in several demonstrations which grew increasingly violent. Socialists called for radical change and eventually several riots broke out in Vienna. Revolutionaries burst into the parliamentary debating chamber and started shooting at conservative members. Stürgkh was unhurt although he had narrowly missed being injured. Gautsch resigned and Emperor Franz Joseph appointed Stürgkh Austrian Minister-President on 3rd November 1911.

Stürgkh had been outraged by the civil unrest and gave little credence to the claims of socialists. He ruled the lands of Cisleithenia autocratically taking as his guiding principal the paternalistic but supreme power of the Habsburgs. Between 1912 and1914, when the situation in the Balkans continued to deteriorate, Stürgkh became closer to the ‘war party’ in Vienna. Opposed by the socialists, and others in the ‘peace party’, Stürgkh became frustrated by their attempts to raise their concerns in the imperial council. On 16 March 1914 Stürgkh adjourned the meetings of the Imperial Council and allowed laws to be passed by emergency decree.

Friedrich Wolfgang Adler was born in Vienna on 9th July 1879. His mother was the writer Emma Adler and his father was Victor Adler a prominent member of the social democratic party. Adler moved to Zurich in 1897 to read physics, mathematics and chemistry at the University of Zurich. This was also the year he joined the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ). Adler continued to work at the university but remained active in politics. In 1907 he became editor of the magazine Der Kampf he then became editor of the Volksrecht newspaper in 1910. Adler became involved in the international trade union movement. In 1911 he abandoned his university work all together and became secretary-general of the SPÖ in Vienna. He became the spokesperson for the left wing of the SPÖ and found himself increasingly at odds with the gradualist and moderate views of the majority of the party.

Friedrich Wolfgang Adler

The problems in the Balkans were of grave concern to the SPÖ. The actions of Stürgkh and his increasingly autocratic rule set both men on a collision course.

Stürgkh, Foreign Minister Count Leopold Berchtold and Chief-of-Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf had long advocated a preventive strike against Serbia. Deeply concerned about the spread of Pan-Slavism in the Bohemian, Carniolan and Croatian crown lands, and irridentist feeling elsewhere in Cisleithenia Stürgkh felt that a show of force in Serbia was the best option to stem the tide of what he saw as socialist anti-Imperialism. This policy was blocked by the ‘peace party’ led by Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the Emperor himself who wished to avoid conflict. The assassination in Sarajevo changed everything.

Once war was declared on 28th July, Stürgkh refused to convoke the parliament while the SPÖ, after a very heated internal debate, decided to support the war. Adler was devastated by the party’s decision. Vehemently opposed to the government’s war policy Adler continued to oppose all measures but was stymied by the lack of democratic means by which to campaign. Parliament was in abeyance and all policy, military and civilian was decided by decree.

Unsupported by his party and with all avenues for legitimate debate blocked Adler was becoming increasingly frustrated. By October 1916 this frustration had reached breaking point. The battles of the Somme and Verdun had killed hundreds of thousands for little or no gain, civilians on the home front were suffering severe malnutrition and the end of the war seemed a distance prospect. Adler identified Stürgkh as the main stumbling block to bringing the war to an end. Stürgkh as an individual supported the war and indeed was an advocate of total war no mater what the costs. In addition, Stürgkh represented the worst of aristocratic Austrian rule willing to sacrifice the lives of working class men and women for the greater glory of the Habsburgs.

On the morning of the 21st October Friedrich Adler armed himself with a pistol and entered the dining room of the Meißl und Schadn hotel in Vienna where Stürgkh was having lunch. Adler entered the dining room and after approaching Stürgkh’s table calmly drew his pistol and shot Count Karl von Stürgkh three times killing him. Adler was instantly apprehended and taken into police custody. The assassination sent shock waves through the Austrian establishment and fears were raised that socialist and communists would use the assassination to foment revolution in Vienna and Budapest. An immediate police crack down on socialist and communist gatherings was ordered and a successor to Stürgkh was quickly found. Emperor Franz Joseph appointed Ernest von Koerber as Austrian Minister-President. This was one of the emperor’s last official acts; he died four weeks later.

The horror of the assassination followed by the death of the emperor shook Austria and fears of revolution were rife. The establishment were keen to play down Adler’s anti-war politics and rumours were spread as to his stated of mind. Court doctors were appointed to have Adler declared insane. This would have avoided the publicity generated by a trial and also give a clear message that anti-war feeling was not a strong political movement but the delusion of fools and lunatics. Unfortunately Adler was quite clearly not insane and no doctor could be found who would declare him so.

In May 1917 Adler’s trial went ahead. The case against him was clear and uncontested he had deliberately shot Stürgkh with the intention of killing him. When Adler stood up to defend himself the worst fear of the establishment we realised. Adler freely admitted his guilt but placed his actions squarely in the context of his anti wars policies. Who was really guilty? Adler who had shot one man or politicians like Stürgkh who sent millions to their deaths? Unfortunately for the authorities, despite the press censorship in place Adlere’s impassioned speech was widely circulated in left wing pamphlets. Frustratingly for Adler, the divisions between the various socialist and communists groups prevented his works from generating any cohesive action.

Adler was found guilty and sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to eighteen years in prison. When the revolution broke out in 1918 he was amnestied and released from prison. He threw himself into the revolution and became leader of the Arbeiterräte (workers’ councils) and a member of the National Council of Austria. By 1921 Adler was secretary of the International Working Union of Socialist Parties and was subsequently active in the formation of the Labour and Socialist International. He served as joint secretary-general of the International with Tom Shaw and then on his own until 1940.

When the Anschluss of 1938 took place Adler intended to stay in Austria to fight fascism. By the outbreak of war however, it was clear that he was in danger of sent to a concentration camp and possibly being shot. Adler fled to the United States.

Friedrich Wolfgang died on 2nd January 1960 in Zurich.

—oOo—