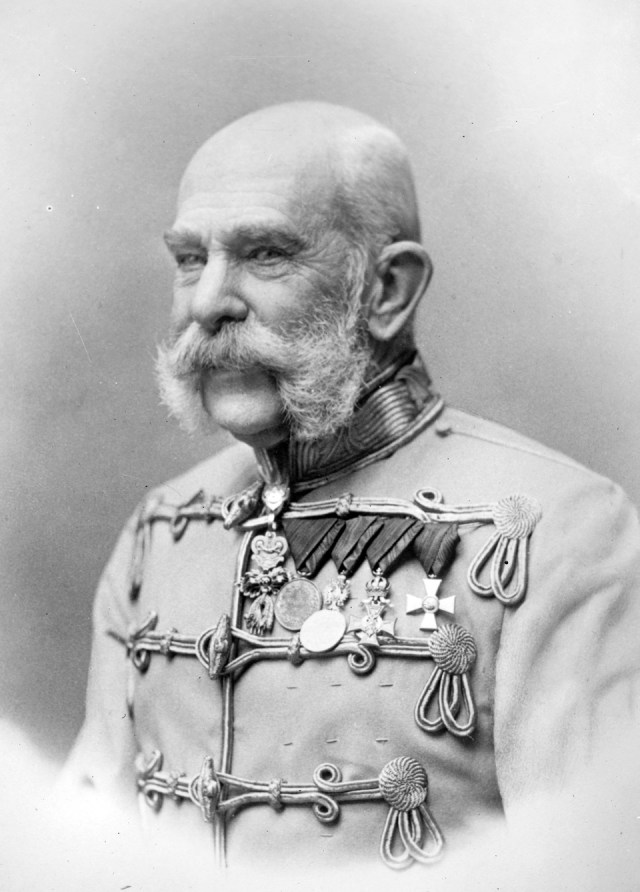

Much had been written about the Ausgleich of 1867 between Austria and Hungary: did it contribute to the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire in 1918; did it emasculate politically Franz Josef; was it inherently unfair to the other nationalities within Austria-Hungary? While there may be an element of truth in all of these statements it cannot be denied that it saved the Empire from an early death after the defeat of Austria by the Prussians at the battle of Königgrätz and ultimately saved Franz Josef from the ignominious fate of having ruled over his “Empire” for only nineteen years.

But what of the charge that the Ausgleich was an arrangement that came about only because of Hungarian hubris? Why did Franz Josef defer to the Hungarians and agree to the terms of the Ausgleich? Was it merely the possibility that the upper-class Magyars would choose to sympathise with the advancing Prussians that made the absolutist monarch accept the compromise? Or were there other existing and more pragmatic reasons?

In 1848 the Magyars were the dominant political and economic group in Transleithania (Szent István Koronájának Országai – Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen). They owned around 90% of the productive agricultural and forestry land which they developed, investing heavily in terms of time and money. The abolition of serfdom in 1848 by Franz Josef had been something of a poisoned chalice for the ‘peasant bourgeoisie’ as there was little or no land with which to start an enterprise and many were saved from destitution by gaining employment as workers on the land on which they had been serfs. This allowed them not only to earn but to remain within their own families and communities rather than be forced from the land. Franz Josef’s abolition decree had made no provision for the freed serfs. The Magyars also invested their wealth in industrial upgrades across Transleithania: by the time of the Ausgleich, the land was already criss-crossed with railways the money for which had come from Magyar landowners rather than Franz Josef. Steel and coal production were improved and the first telegraph systems started to appear connecting towns and cities across Transleithania. Investment in new agricultural practices and industrialisation were more advanced in Transleithania than its western counterpart.

With an Austrian economy buckling under the cost of defeat by the Prussians Franz Josef needed a political and economic miracle; he received it with the signing of the Ausgleich.

The establishment of the two autonomous economies meant that Austria and Hungary could officially trade with each other, with separate fiscal policies. This created an income to the Hungarian government which allowed for a reduction in taxes and a freeing up of income which could be invested and thus further strengthen the Hungarian economy. The Austrian economy, which was flagging by contrast, due to a lack of investment, was helped by the Hungarian parliament on several occasions when it helped to pay off the Austrian governments debts.

The Ausgleich may have had it flaws, most notably in ignoring many of the other people of the Empire, but while it was shaped by Magyar pride and ambition it was all too readily accepted by an embattled emperor. It has been said that had Austria not been defeated by the Prussians the Ausgleich would never have been signed. It could equally be argued that had Franz Josef managed the economy of Cisleithania better the Ausgleich would have been a very different compromise.

——————–oOo——————————